Towards ‘housing for all’ through peoples’ participatory process

4th October 2020, Sunday Times

Towards ‘housing for all’ through peoples’ participatory process: Watapuluwa Housing Scheme and the pioneer contribution of Minnette de Silva

By Chanaka Talpahewa

“In the past 75 years [from 1875-1950] the population of Ceylon has trebled. Yet typical living standards, while low in comparison with the West, have been maintained and almost certainly improved; at present they are among the highest in Southern Asia.”

– Economic Development of Ceylon

(A report authored by the World Bank mission which visited Sri Lanka in 1951 and which was published in 1953)

This above extract provides a snapshot of the status of the population increase the newly independent Sri Lanka (or Ceylon) was facing. Unlike the indigenous monarchical times, the rapid and fundamental changes introduced through the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms had an immediate impact not only on the economic development but also of the socio-cultural fabric of the island.

Features such as advocating a laissez-faire economy, encouragement of free trade, abolishment of Government monopolies over cinnamon cultivation and trade as well as the traditional institutions such as land tenure by accommodessan (the granting of land for cultivation, proof of land ownership through legal documents such as deeds as opposed to its outright sale) and rajakariya system resulted in the economy changing from primarily a subsistence agriculture to more of a plantation mercantile with a corresponding socio-cultural changes. The traditional barter system was replaced with the more widespread usage of currency. The coordinated construction of roadways and railways beginning with the Colombo-Kandy road in 1820 by Governor Edward Barnes and the Kandy-Ambepussa railway line in 1858 by Governor Henry Ward, although to facilitate the plantation sector, significantly contributed to the agglomeration of more people in convenient central locations resulting in the development of townships.

Post-Independence Urbanisation

The increasing growth of urban centres prior to and after Independence, was mainly due to the influx of people from villages to the towns, for ‘convenience’ as well as ‘better prospects’, despite the lack of corresponding increase in basic urban services. After Independence, the shortage of urban housing became an ever-expanding issue for the Government and providing an effective resolution with a sound rationale was of paramount importance.

This resulted in aggregated interventions on the part of the Government in the urban housing sector. As a result, in 1949, the Housing Loan Act was enacted and the Housing Loans Board (HLB) was established. The main purpose of the Housing Loans Act was to promote private sector investments in housing for the middle and working class.

Realising the growing importance of addressing the issue of housing, in 1953, for the first time, the subject of housing was gazetted and given a Cabinet level recognition by the new Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala with the appointment of Senator Kanthiah Vaithianathan as Minister of Housing (later Minister of Industries, Housing and Social Services due to the resignation of the Minister of Industries G. G. Ponnambalam). This resulted in the creation of the Department of National Housing in 1953 to provide housing through Government delivery mechanisms and the National Housing Fund in 1954 to provide housing loans to middle-income residents. To ensure necessary legislation, the National Housing Act was enacted in 1954. According to Vaithianathan “the Government’s aim, however chimerical it seems, however Utopian as a concept, is a house – owning democracy.”

The Government envisioned a two-pronged approach. Firstly, to build separate houses and blocks of flats for middle-class and working class families to be alienated on schemes of rent-purchase and secondly, to provide finance and assistance by way of acquisition of land for individuals and Building Societies to build houses for themselves and to provide loans at graded rates of interest, particularly, to land-owning low-income people to construct to construct houses for themselves.

Under these initiatives the first example includes the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme in Kandy, which by far the most outstanding example, Bambalapitiya Flats, Armour Street Flats and Kiribathgoda Housing Scheme.

Watapuluwa Housing Scheme in Kandy

The most remarkable pioneering example of a participatory approach witnessed in Sri Lanka was the planning and the execution of the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme Project in Kandy launched in 1955. It was a trailblazing and innovative project that was decades ahead of its time. For the first time in Sri Lanka, and perhaps in the world, an inclusive beneficiary participatory process/approach was adopted in housing.

By the 1950s Kandy was the island’s second largest city with many public servants stationed there. The most acute problem faced by majority of these persons was the dearth of Government quarters and the lack of private housing. This resulted in a preponderance of public servants being compelled to live in dilapidated conditions in less than desirable surroundings. In 1954 Kandy Housewives’ Welfare Association was started mainly to address the increasing cost of living, but was also faced with the issue of lack of adequate housing.

The latter led to the formation of Kandy Public Servants’ Building Society in 1954 with a Board of Directors headed by N. Sivagnasundaram, Additional District Judge, as the President, and Lorna Wright and Brixious Samarasinghe as Co-Secretaries. The Society made successful representation to the then Government to acquire 88 acres (according to some records 95 acres) of the Hancock Estate at Watapuluwa to establish a ‘Housing Scheme’ when the term itself was not in vogue. Situated within the Municipal limits of Kandy, the estate, adjoining the Ceylon Tobacco Company premises, belonged to late W. R. Hancock.

The project went on to shape the national policy on public housing when Lorna Wright convinced the Commissioner of National Housing L.V. Wirasinha and Minister Vaithianathan, for special dispensation to obtain a salary loan to buy land and build own homes for Kandy Kachcheri’s public servants. in the Kandy Kachcheri, which was then not provided for. Wright’s successful argument was as to why a two-year salary loan for land and housing cannot be considered if the Financial Regulations permit loans for purchase of vehicles. Today, public servants’ housing loans have become a Government policy.

Funding for the laying out of the land and the construction of houses were on a 25-years rent-purchase-ownership arrangement, where approximately 230 beneficiaries had a construction funding up to two-year salary loan ranging from Rs. 10,000 upwards to approximately Rs. 30,000. This project can be considered as an example where the authorities and the beneficiaries worked in tandem, complementing each other. Thus, the first Government Public Servants Housing Scheme commenced in June 1955 with the participation of the then Minister of Housing.

Minnette de Silva, one of the best-known architects in the country, incidentally, hailing from Kandy, was appointed as the architect of the project.

The Forgotten History

Minnette de Silva was the first woman in Asia to become an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. As a student (and was the youngest to attend) she had the rare distinction of attending the first CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne or International Congress of Modern Architecture) that took place after World War II in Bridgewater, UK. This provided her with the rare opportunity to observe (and also contribute) how the greatest architectural minds of that time identified the issues that arose in massive reconstruction efforts and devised methodologies to address and overcome these.

She also became CIAM’s first Asian delegate representing Ceylon and India. Minnette, together with Mulk Raj Anand (an Indian writer and thinker) and her sister, Anil de Silva, founded MARG (the Modern Architecture Research Group) and started a journal of the same name, the seminal South Asian arts magazine, Marg: A Magazine for the Architecture and Art in October 1946. She was a Contributing Editor and displayed her innovative spirit together with her academic and scholarly skills at an early age. Later in life she ventured, amongst others, into architectural history, urban planning, design and craftsmanship, archiving, conservation and teaching.

On her return to Sri Lanka she set up her practice in Kandy, at that time, one of the two women in the whole world to do so in the then male dominated profession. She was a close friend of Le Corbusier, one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century architecture and it is said that it was she who convinced Ulrik Plesner, the Danish architect who famously teamed up with Geoffrey Bawa (initially he teamed up with Minnette for a year) to visit and later work in Sri Lanka.

She was the first Ceylonese architect to endorse what Ananda Coomaraswamy (by his Open Letter to the Kandyan Chiefs) said in 1905 on the importance of preserving traditional crafts by using traditional materials and local craftsmen and technology for contemporary buildings. Minnette was among the first to amalgamate knowledge acquired from the West with the building traditions and technology of Sri Lanka and India. Her architectural style is considered syncretic Tropical Modernism and she also pioneered the architectural movement known as Regional Modernism.

The building society itself had varied and a mixed set of members. Although being Public Servants, the membership consisted of those hailing from different professions, grades and levels, ethnic groups, religions, social strata and political and ideological affiliations. As a result, Minnette faced the challenge of housing a varied group of individuals (households) within the same development while minimising the costs. The planning was done adhering to the stipulated rules, standards, regulations, controls and laws.

An examination of the planning process of the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme undertaken by Minnette displays her pioneering vison. Firstly, Minnette’s emphasis was to use the site economically as possible by effectively using the slopes thereby minimising the necessity for the cutting of the land (slope modification), whilst preserving the natural environment as much as possible. This gives an insight to early thinking of Minnette on Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation, which certainly was not thought of in the 1950s.

Secondly, observing the repeated failures of mass housing projects due to inappropriate priority given to financial and political considerations, resulting in end-user dissatisfaction due to disregarding of recipient requirements and preferences, Minnette placed primary focus on the end beneficiary or the user of the scheme. In order to do so she developed a preliminary questionnaire mainly to identify the different categories of house builders according to their income capabilities etc. She went further to develop a second questionnaire to determine the socio-cultural status. After categorising the beneficiaries Minnette had detailed discussions with different groups (today we call it Focus Group Discussions or FGDs), for example, like the Rs.10,000 to Rs.17,000 cost of house groups, to fine-tune the requirements.

Minnette de Silva on site at Watapuluwa in 1957

Pursuant to the questionnaire and the discussions, Minette developed 5 or more type plans to suit the topography of each site with 6 or more sub-types to suit the cost and wishes of each member accounting to a total variation of approximately 50 sub-types together with community amenities such as nursery school, clinic, park etc. The Bills of Quantities were worked out in such a way that the removal or addition of a wall or roof were calculated per cubed unit (i.e. the cost of a 4 ½ brick wall per square feet per house type) enabling a simple formula for adjusting the cost of variations. Each member family was asked to fill in a questionnaire about their preferences etc., within the cost limits.

In 1957 the plots were divided as per the Master Plan and the work went ahead. She always attempted to use traditional material in the construction as much as possible. In her way of planning Minnette ensured that the beneficiaries also had responsibilities as they had to pay for communal services like roads, water etc. and the maintenance of an office. Certainly, a pioneering Peoples’ Participatory Process at a time when such things were not heard of and the term itself was not even coined.

There was a disruption in the work due to the change in political will to support the Housing Scheme after the change of Government in 1956. However, the issues were sorted and the project was completed in 1958. One of the unique features of the Watapuluwa Housing Scheme is that, unlike standardised mass houses in today’s Housing Schemes, no two houses are alike. Another very positive outcome, which is very relevant in today’s context, is that ‘there is a tremendous felicitous community spirit with a mix of Sinhala, Tamil, Muslim, Malay and Burgher families, who whenever in need go to each other irrespective of ethnic or religious differences.’ Minnette’s participatory approach (one can see when perusing some of the questionnaires where she has also ascertained the religious preferences i.e. place to worship etc.) has similarly paved for ethnic harmony and peaceful co-existence way before these terms became buzz words in the development field.

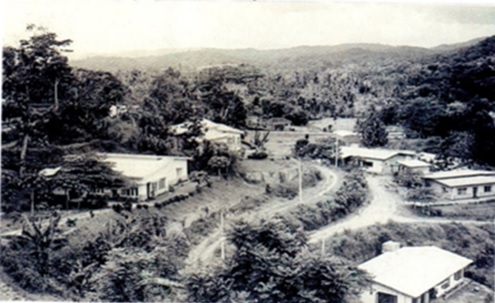

Watapuluwa Housing Scheme under construction

Lessons Learnt

Watapuluwa Housing Scheme, although somewhat unheard of today, is a unique Sri Lankan experience and stands out as an epitome of qualities we recognise in social housing such as economy and efficiency of delivery, sensitivity to location, fusing modernist principles with traditional local craftsmanship, conserving the environment (including climate change issues), giving emphasis to greenery, focusing on DRR, collaborating with the beneficiary (inclusivity) in the designing and construction, utilisation of local labour etc. Undoubtedly it has stood the test of time and has given us many valuable lessons of effective peoples’ participation, whether green field or reconstruction, for us to learn and follow in our quest towards meeting the goal of ‘Housing for All’ in a sustainable, effective and efficient manner.

It is also clearly indicate that Minnette de Silva was way ahead of her time and should be recognised as the pioneer who introduced the inclusive beneficiary participation, whether it is known today as the Peoples’ Participatory Process, Peoples’ Participatory Approach, Peoples’ Process, Community Architecture (as she would call it) or by any other term, in housing construction in Sri Lanka and perhaps in the world. This was a remarkable achievement for woman, particularly an Asian woman, in a male dominated era in a male dominated profession.

(Author wishes to acknowledge that articles referred to and interviews conducted in writing this article are not mentioned due to lack of space)