Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in Sri Lanka’s urban areas: lessons from the State of Sri Lankan Cities Project

5 May 2018, Colombo, Sri Lanka. The Government of Sri Lanka is committed to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But what does this mean for Sri Lanka’s cities? Drawing on preliminary analysis from the State of Sri Lankan Cities Project, this article explores the opportunities and challenges for Sri Lanka’s urban policy makers as they work towards achieving the SDGs.

The Sustainable Development Goals and Sri Lanka’s Cities

The seventeen Global Goals for Sustainable Development represent the agreement of world leaders on a shared vision of a sustainable future. The goals were agreed by the 193 countries of the United Nations General Assembly in 2015, and will shape member states’ development strategies towards achieving a sustainable future by 2030. In this context, Goal 11 deals specifically with the attributes of sustainable cities, highlighting a range of issues, from the liveability of cities to their resilience to climate change.

The Sri Lankan government has demonstrated a strong commitment to achieving the SDGs, including the vision of sustainable cities. Correspondingly, sustainable urban development is a feature of flagship Government of Sri Lanka policy documents, including Vision 2025 and the Public Investment Programme 2017-2020.

The State of Sri Lankan Cities report, to be launched later this year, will provide an important assessment of the country’s urban spaces against the SDGs and, in doing so, will support on-going government activities to achieve them.

Opportunities to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in Sri Lanka’s Cities

Preliminary analysis conducted for the State of Sri Lankan Cities project shows the enormous potential of Sri Lanka to achieve SDGs related to cities. A key strength lies in the prevalence of urban green and public space across the country, which has been revealed through spatial analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery and the production of detailed land use maps for the nine provincial capitals.

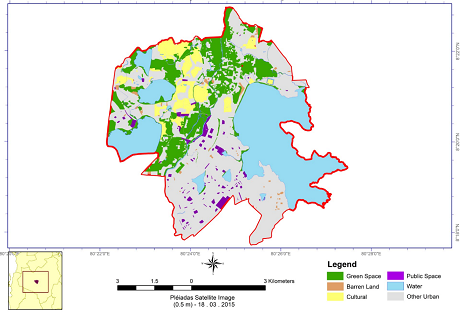

The provincial capital of Anuradhapura is a good example of a city with an abundance of green and public space. A large proportion of the Municipal Council area is green space (see Fig 1, in green), which includes protected areas, such as forest and wetland, as well as large bodies of water. The ancient capital is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, home to cultural and historical sites of international significance (see Fig 1, in yellow); these sites include large areas of green space, and often also incorporate water features. In addition, there is a significant stock of other types of public space, including squares and playgrounds (see Fig 1, in purple), as well as pockets of unutilised open space in the form of barren land (see Fig 1, in brown).

Fig 1: Land use map of Anuradhapura Municipal Council

Source: UN-Habitat

Protecting and upgrading these public and green spaces contributes to a range of SDGs. Most obviously, public and green space directly relates to the Goal 11.7 to ‘provide universal access to safe, inclusive green and public spaces’. In addition, a key ecosystem service provided by green spaces is to strengthen urban resilience to disasters and climate change – an important issue related to multiple Goals and other international agreements. As a case in point, wetlands in the Colombo area have been shown to be particularly important to the city’s flood resilience. Urban wetland parks, such as Diyasaru (Fig 2), also contribute to the Goals by providing areas where ecotourism can be promoted (Goal 8), and where urban residents can enjoy recreational activities, contributing to their health and well-being (Goal 3).

Fig 2: Diyasaru Wetland Park

Source: UN-Habitat

Challenges to achieving the SDGs in Sri Lanka’s Cities

There are also challenges to achieving the SDGs in Sri Lanka’s cities. A major issue identified as part of the State of Sri Lankan Cities project is related to rapid urban sprawl, which has occurred in many Sri Lankan cities since the 1990s.

Low density urban expansion is widely considered undesirable, because it increases the costs of providing public services and utilities, such as sewerage, waste disposal, and public transport. The universal provision of these services and utilities are key components of Goal 11.

As well as challenges relating to the provision of services, urban sprawl can also leave populations more exposed to disasters and the impacts of climate change, presenting an additional challenge to achieving the Goals – particularly, those relating to health and wellbeing, climate action and disaster resilience.

A key issue is that urban sprawl often involves rapid land use change from green space, such as wetlands and agricultural land, to impermeable urban land uses. In Colombo, this pattern of land use change has reduced the natural flood drainage capacity of the city by up to 30 per cent in the last ten years. This declining capacity has synergised with shifting rainfall patterns resulting from long-term changes in climate, which has further increased flood risk, according to Sri Lanka’s National Adaptation Plan. At the same time, urban sprawl has resulted in rapid population growth in peripheral, flood-prone areas, exposing an ever-greater number of people to hazardous flood waters.

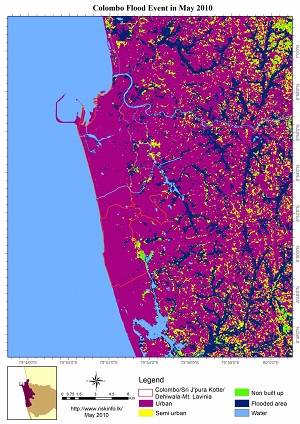

The trend of increasing urban flood exposure is being investigated in the State of Sri Lankan Cities Project through time-series spatial analysis of urban growth and the mapping of flood extent. The preliminary analysis of the Colombo area has involved mapping the extent of the 2010 flood (considered one of most severe flood events to impact the city) against urban extent to determine which areas are most at risk (Fig 3, left). The team also mapped the 2010 flood extent on to urban extent in 2017[1], to give an idea of what would happen if a 2010 magnitude flood occurred in today’s highly urbanised landscape (Fig 3, right).

This analysis has revealed two key trends: first, the 2010 flood extent exposed suburban areas to a much greater extent than central areas; second, that urban expansion between 2010 and 2017 has meant that a larger urban area would be exposed if a 2010 magnitude flood occurred in 2017. It should also be noted that land use change during 2010-2017 has reduced the flood drainage capacity by converting green space to urban land use, potentially exacerbating the impact of a flood of 2010 magnitude.

Fig 3: 2010 flood inundation and urban extent 2010 (left); 2010 flood inundation and urban extent 2017 (right)

Source: UN-Habitat

The challenge of accurately assessing Sri Lanka’s cities against the SDGs

The first article in this series highlighted issues relating to how ‘urban’ is defined in Sri Lanka. This definitional challenge also has implications for assessing cities against the SDGs. According to preliminary analysis by UN-Habitat, under 20 per cent of the built-up area associated with Sri Lanka’s provincial capitals are in areas administratively defined as urban; the remainder are officially classified as rural.

This disparity between the administrative urban area, and the much larger area showing urban spatial characteristics, presents an important dilemma in assessing SDGs in Sri Lanka: which measure of ‘urban’ should be used?

This question is particularly pertinent given that it is in the rapidly changing areas – which are often administratively classed as ‘rural’ – where Sri Lanka’s urban future will increasingly be defined. These are areas that may currently enjoy an abundance of green spaces, but face challenges in achieving sustainable forms of urban development as they grapple with rapid land use change, limited service coverage and a range of other issues. It is imperative, therefore, that progress toward the SDGs is closely monitored in such areas to secure a sustainable urban future for Sri Lanka

The State of Sri Lankan Cities Project, funded by the Government of Australia, is implemented by UN-Habitat in close collaboration with the Government of Sri Lanka from 2017- 2018. Key project partners include the Sri Lanka Institute of Local Governance, Urban Development Authority, Local Authorities of the nine Provincial Capitals and the Asia Foundation.

[1] A severe flood also affected Colombo in 2016. However, comparable spatial data for this event was not available during the UN-Habitat analysis.